I’d been meaning to read Patrick Marnham’s excellent biography of Mary Wesley, Wild Mary, for ages, and I'm so pleased I finally got round to it. It is a fabulous book - so well written and readable that one hardly notices it’s there, so immersed is one in the life of its subject. This is a state to which all biographies should aspire, I feel.

I’d been meaning to read Patrick Marnham’s excellent biography of Mary Wesley, Wild Mary, for ages, and I'm so pleased I finally got round to it. It is a fabulous book - so well written and readable that one hardly notices it’s there, so immersed is one in the life of its subject. This is a state to which all biographies should aspire, I feel.And what a subject! I’d read all of Mary Wesley’s novels when they first appeared in the 80s and 90s and enjoyed them enormously, though I confess that my younger self was always slightly incredulous about the kind of things Wesley’s characters were supposed to have got up to in the War years. Having naively believed that it wasn’t until the swinging sixties that sex was invented - and with a view of middle-class mores in 1930s/40s Britain coloured by the likes of Brief Encounter and The Diary of a Provincial Lady - while delighting in the exploits of Calypso, Rose et al, I did rather assume that they were perhaps a little far-fetched.

Well, of course, this was terrifically blinkered view, as Wild Mary amply confirms. Wesley’s love life was if anything more complicated, abandoned and generally ‘wild’ than those of any of her fictional characters. As everyone knows, she published her first novel, Jumping the Queue, at the age of 70, and then went on to write nine more deliciously entertaining best-sellers. I found her own story even more fascinating and extraordinary than her novels. She was by any standards a most remarkable woman.

As soon as I’d finished Wild Mary, I re-read Not That Sort of Girl and The Camomile Lawn and enjoyed them, I think, on quite different levels with the dubious benefits of Age and Experience! They are joyously breezy and perceptive and leave one refreshed and fizzing with Wesley's infectious spirit.

As soon as I’d finished Wild Mary, I re-read Not That Sort of Girl and The Camomile Lawn and enjoyed them, I think, on quite different levels with the dubious benefits of Age and Experience! They are joyously breezy and perceptive and leave one refreshed and fizzing with Wesley's infectious spirit.

What a strange thing it was, though, reading these three books immediately after finishing Kathryn Harrison’s Envy. A very thought-provoking juxtaposition. For here, interestingly, are many of the same themes – love and desire, adultery, incest, twins, families under threat, and the survival of relationships against all odds and across the decades.

What a strange thing it was, though, reading these three books immediately after finishing Kathryn Harrison’s Envy. A very thought-provoking juxtaposition. For here, interestingly, are many of the same themes – love and desire, adultery, incest, twins, families under threat, and the survival of relationships against all odds and across the decades.

In Envy, a single ill-advised sexual act threatens to destroy an entire educated, liberal, twenty-first century world. Yet in Mary Wesley’s 1930s - as for Rose in Not That Sort of Girl, clomping round her chilly country house in her sensible shoes, buttoned-up blouses and tweed skirts, her husband Ned (and lover Mylo) overseas - incidental sex can happen to anyone, at any time (almost while they're not looking!) and though there may be a few inconvenient ramifications, the results are rarely catastrophic. All part of the war-time spirit. When Rose is ill in bed, her old friend George pops round each day to read to her from War and Peace and one afternoon has to tell Rose the news that her (not terribly beloved) father has died:

‘The rest of Rose’s declaration was drowned by sobs. George saw himself gathering her in his arms to comfort her, lashing out with his foot to kick away the scalding hot-water bottle, pushing aside the cats. It seemed simpler to console Rose in her bed; she would not catch cold that way. Rather warm though. Easier if he took off his trousers. This is not really my style, he thought, but all the same it’s pretty good and my word it’s oh, ah, oh. ‘Heavens, Rose, I did not really mean to do that. I hope you don’t think I set out to - I hope I’ve not made your pneumonia worse – here, hang on while I retrieve that hot-water bottle, oh, good, it’s still warm, oh, Lord, look at the cats, what an unfeeling . . . .’ ‘Stop burbling.’ Rose straightened the bedclothes as he got back into his trousers, pulled her nightdress down and the sheets up, settled the hot bottle by her feet, reached for a comb, ran it through her hair . . . [Later] when people discussed tonics, pick-me-ups after severe illness, she kept to herself the prescription of a quick dip in bed with someone you liked but were not in love with. A short shock of sexual astonishment which could make you feel surprisingly well and high spirited.’

Well, well – who’d’ve though it, eh? I don’t know what my grandmother would have made of it! It wasn’t that Mary didn’t feel pain and guilt, jealousy and anguish as well as pleasure in her many relationships. She most certainly did. 'Wild' she may have been, but unfeeling she was not. And where she truly loved, her love survived everything, even death. But she never let convention or other people’s expectations get in the way of her living and loving on her own terms.

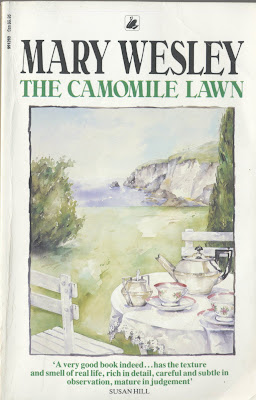

I’ve reproduced the covers of my own twenty-year-old copies of her novels here because these were the designs – specifically Susan Moxley’s evocative watercolours – which Mary Wesley wanted for her books, and I don’t think they’ve been bettered in the subsequent paperback reissues.

3 comments:

Wild Mary was absolutely the best biography I read last year and for me it brought to life a time that my mother had described to me so vividly on many occasions. She had worked in West End theatres throughout WWII and was, thankfully, extremely broadminded, non-judgmental and more or less unshockable. She said that the '60s reminded her in many ways, at least as far as relationships were concerned, of what had been happening in wartime ... but with more reliable contraception!

I have all Mary W's novels in the edition you mention. They were my mother's, which makes them all the more special to me.

Ah, well, there's the difference, D, and the reason behind my sheltered upbringing. My parents were children during the War, and my grandparents were shockable, judgmental, Methodist country-folk. They didn't care for the 1960s one little tiny bit, either!

On the subject of liberal parents (or mothers, to be more precise) ... my daughter always tells me (and anyone else who will listen), that the big disadvantage of having a liberal parent (or parents) is that you have nothing to rebel against when you are growing up.

I think there may be some truth in this because, while there were a few arguments, my daughter's teenage years were not, on the whole, marked by lashings of angst, slammed doors, grunts or silences. And I don't remember her ever saying 'You don't understand me.'

I did rebel, not against my mother, but against my father who was - when at home - very strict and very miserly indeed. (Far stricter than any of my friends' fathers, in fact.) He was, however, a completely different character when he was away from home, where he was Mr Charming and Mr The Drinks Are on Me.

Oh well, grist to a writer's mill, I suppose. And now I must think about something uplifting, otherwise I will be grumpy all day.

Post a Comment